This fall I

have been teaching a study unit on Game Design at our Masters in Digital Game

at the University of Malta. This is the first year we teach the course, and we

are starting with a small group of students. We can be flexible and find individual

solutions in case our structure isn't optimal this first time around. Except me

teaching at the masters' there is Rilla Khaled who teaches game design with me,

there is Gordon Calleja and Costatino Oliva who teaches game analysis, and

there is Georgios Yannakakis who, together with two teachers from ICT, teaches

computing science for game development. We also have a fourth strand in the

masters, which is commercialization and project management. This is taught by

industry professionals, this year by the CTO of TRC.

I have been

teaching game design and related subject since 2004, but somehow it always

feels like it is the first time. During the summer of 2012 I planned this

introductory course in game design, but as soon as got hold of the students'

contact details I sent out a survey to them to get an idea about previous

experience in both the playing of games and of developing them.

This is the

short description of the course:

"The

course address the role of the game designer, the structure of games, how to

work with formal elements as well as dramatic, and ways to approach system

dynamics. Students work in groups and conceptualize and prototype smaller

games."

Concerns

I had

several concerns while I was planning the course. How to balance theory and

practice? Were to begin - which topics need we start with, and which can wait?

How do we make sure the group dynamics work out? And what about creating a safe

environment for experimentation despite that their work is graded?

I'll go

through my main concerns, listing them, and describe how I aimed to solve them.

Then, I'll tell you how it went!

- What to teach them - where do I start, and in

what order should I place the content?

I decided

to use a course book as a basic skeleton for the course. I had, unconsciously,

already decided to use Tracy Fullerton's book Game Design Workshop, but just in

case I would like to change my mind I browsed through the rest of my design

library. I stuck with Fullerton's book because it is the one that put most

weight on prototyping and play-testing, and does so in a very concrete way.

This agrees with how I like to work in design. As recommended reading I added

chapters from other books for certain topics, such as Bates' chapters on what

project documents are useful in game productions.

Also on the

list of recommended reading is Brathwaite's “Challenges

for Game Designers”.

It has an excellent and condensed introduction chapter defining important terms and approaches. The remainder of the book contains design challenges/exercises for different types of games and game contexts.

Another one is Koster's "A Theory of Fun". This book has had a large impact on the vocabulary used in the area of game design. Koster just gave a speech at GFC Online (October 2012) taking the perspective of "ten years after" - that is, ten years after the publication of the book. The slides for the talk are here: http://www.raphkoster.com/

Yet another great book on game design is Schell's The Art of Game Design: A book of lenses. If I had not used Fullerton's Game Design Workshop as the main course book I would have used this one.

It has an excellent and condensed introduction chapter defining important terms and approaches. The remainder of the book contains design challenges/exercises for different types of games and game contexts.

Another one is Koster's "A Theory of Fun". This book has had a large impact on the vocabulary used in the area of game design. Koster just gave a speech at GFC Online (October 2012) taking the perspective of "ten years after" - that is, ten years after the publication of the book. The slides for the talk are here: http://www.raphkoster.com/

Yet another great book on game design is Schell's The Art of Game Design: A book of lenses. If I had not used Fullerton's Game Design Workshop as the main course book I would have used this one.

- How to

achieve a balance between theory and practice? Students need the practice to appreciate the

theory, and they need the theory when working practically. (This is something

Jesse Schell have been blogging about too)

I had seven

seminars and seven workshops to work with. Part of the first one would go to

overview and introduction, and the end would be the final seminar. I considered

what they absolutely HAVE to know about the design, and what they MUST learn to

do and think about when designing. I plucked those topics, and then added

workshops where they would apply the knowledge in the topics. This meant that I

was not using the order in Fullerton's book, but I could still use the full

chapters for different seminars.

Given the large

amount of time that it would take for the students to complete the assignments

they needed to do in order to practice game design I aimed to only add the absolutely

necessary texts as reading assignments. Besides the selected chapters in Fullerton's

book I only added two texts as mandatory reading: one about Hunicke and LeBlanc's

MDA model and the other about Dorman's Machination framework.

In the

first seminar the students got to choose from the course literature about which

texts to champion. This text, they would in one of the seminars present to

their co-students and prepare a discussion about.

There is a list of the topics we had at the seminars, and a list of

workshops and assignments in the end of this post.

- How do I make sure that they early get

practical experience of designing different types of games? (There is a risk of individuals

getting so immersed in one idea or problem that they do not want to focus on

anything else.)

It turned

out that this particular group of students all were graduated computing

scientists and many of them had partaken in game development projects. I

decided that even though they would be able to create digital prototypes from

start, I would encourage them to stay with pen and paper. This way they would

be able to quickly try several different designs, and they wouldn't get

distracted by coding problems. During the first three weeks they prototyped

three different games. Then, they got to choose one of them to develop further.

This game was play-tested and iterated for three more weeks. I hoped that this would help them to have

their focus on the core design as well as on the experience their certain

design might result in for the player.

- How do I cater for good group dynamics in the

student groups? (Or at least be prepared to sort out things if it becomes

terrible.)

I planned

for having two occasions for group division. In the first seminar I divided

them into two groups using coin flips, thus making a random group division.

Then, after having made their first three game designs they would be able to

change groups for the second half of the course. This would make sure that if

two persons who for some reason cannot work out their differences would be able

to change groups. In the one of the game design exercises a beginning task was

to fill in a Meyers-Briggs Personality test - I added it in as part of the

exercise so that they might use personality properties of some kind of system

as part of the design of a game that contains characters. I hoped for a

secondary effect where they would be aware of each other's strengths as

individuals when working in groups. In my experience shortcomings of others are

easier to accept and overcome when one have concrete knowledge (or some kind of

belief or interpretation) of others strengths.

- On Malta, student's work is graded. How would I make sure to create an environment where student feel that they can be creative, where they take risks, and where they are not mentally frozen by performance anxiety?

I divided

the assignments I gave into those that would be graded and not graded. All the

design exercises except the final deliveries were to stay without grade. At the

same time, the final deliveries would report on and be a result on what they

had been producing during the course. But then, they would have been able to

pick one of three designs they liked best, and had been able to iterate that

design several times.

How it went

I have the

impression that the course went well. The students had a 100% attendance. They

delivered 100% of their assignments, and not a single one of them was late. For

me this is the very first time that has happened. The group of students was very

small, and they all had responsibilities in the seminars, so that could have been

a reason. But still: Highscore! They also volunteered for extra work, and went

the extra mile of doing the extra exercises. When the students had handed in their final

assignments (an individual short-paper, a production report, a game design document

and a game prototype) I was quite impressed by their work. They had managed to

create games, describe how they did it, showing that they had understanding for

the process. I had played the games with a colleague the day before the

seminar, so I could get them some feedback on that too. Next year I'll schedule

more time for playing the students' games though, in order to get time to

explore all features. For their individual short papers I had asked them to

define an important design problem and give suggestions for how to explore the

same. Here, they all had picked very

interesting and relevant topics, which we spent most of the last seminar

discussing these.

Ending discussion

I had

created an online survey for the students to fill in, but some topics I wanted

to ask them about face to face. In the last seminar we spent half an hour

discussing the course. What had worked and what had not worked?

It seems that the balance between theory and

practice had worked well - the students had recognised that they were, in the

workshop, practising the same skills and topics they had been discussing in the

seminar the same day.

The workload

seems to have been fairly well adjusted. I was worried that I had given them

too much (see list of assignment and bear in mind that they had 3 other courses

running in parallel). But they had appreciated the incremental nature of the

workload, that they got week-sized chunks of work, and then one week to

assemble the work into their final deliveries. They also said that they liked

to have this 4 hour marathon (2 hours seminar, 2 hours workshop) rather than

dividing their day. I had been worried about that too.

They were

generally happy with the clarity of instruction, but would have wanted to learn

more about table top RPGs before getting the task of designing one. Next year

that could be a part of assignments.

They had

really appreciated the guest lecturer from TRC, Jade Pecorella, who talked

about how game design is communicated and documented in the projects where she

works as a designer.

They had

also liked the way they were each championing parts of the course materials, so

that (no offence they hastened to say) not only the professor talks all the

time, and that it is easier to learn when one has to explain to someone else.

It was

difficult to squeeze out something negative of them, but that's what the

anonymous survey is for. I told them to think about it as a play-test. If I

don't know what's wrong, I can't fix it.

The next

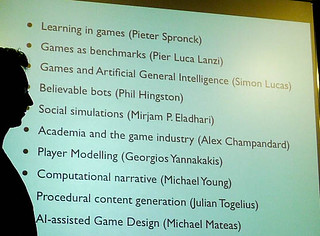

course I will teach will be focussed on AI based game design and prototyping/sketching

tools and methods. I really look forward to it. I need to make sure that even

if this group are all computing scientists I need to design a course that is

meaningful and useful for non-computing scientists too. By the way, there is a

quite common understanding that computing scientists or 'coder types' would be

less creative than others. This is wrong. Not that we would be MORE creative.

Just that we are just as creative as the rest of the population. At least, this

is my belief after having witnessed the process of game creation in this group

that consists only of computing scientists. (Also - take a poet. Teach her how

to program. Will she be less creative when she has more knowledge?)

***************************************************************

List of topics

The list below is presented in the order they appear

in the course.

Brainstorming

and Conceptualization methods

The role of

the game designer

The

structure of games

Prototyping

methods

Formal

Elements

MDA - a

formal Approach to Game Design and Research (paper)

Working

with Dramatic Elements

Play

testing

System

Dynamics

Functionality,

Completeness and Balance

Simulating

Mechanics to Study Emergence (paper on Machinations)

Revisiting

Brainstorming and Conceptualization (creativity in the long run discussion)

Game Design

Document (Communicating Game Design)

*****************************************************************

List of mandatory Assignments

Presenting

chapters from the course book and papers to the seminar (in seminar and

assignment) (graded)

Brainstorming

Exercises (in workshop) (not-graded)

Writing my

first treatment (assignment) (not-graded)

Making my

first paper prototype (in workshop & assignment) (not graded)

Modifying a

Battleship Prototype (in workshop) (not graded)

Making a

Table top role-playing game prototype (in workshop and assignment) (not graded)

The first

play-testing and writing a play test-script (assignment) (not graded)

Play-testing

using the other group as testers (in workshop) (not graded)

Writing the

game design document (in workshop and as assignment) (graded)

Writing

your production report (assignment) (graded)

Finalizing

your prototype for delivery (assignment) (graded)

Writing

your short-paper (assignment) (graded)

The text

seminar - presenting and questioning a colleague's text. (At the end of the

course) (not-graded)